- Home

- Brian K. Fuller

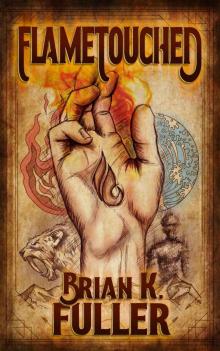

Flametouched Page 11

Flametouched Read online

Page 11

“So at fourteen, three years from his majority, young Davon inherits an indebted, bankrupt estate. Most boys that age would simply fall apart. Not Davon. He fired all his servants and cooked, cleaned, gardened, and managed his family’s estate for four years, utterly alone, until he had paid back all of his father’s debts. He has since turned Frostbourne into one of the most prosperous estates of its size in the Kingdom. Believe me, dear, when I tell you that I had my people keep an eye on Frostbourne for a long while, and what Davon accomplished there was nothing short of astounding. He is a brilliant man.”

The Queen paused, and Arianne tried to take it in, but the Queen plowed on before she could sort out her feelings.

“So enter young Emile Ironhorn of questionable reputation to everyone except the isolated Baron Davon Carver, now with a prosperous estate. She is beautiful, she is accomplished, and, it appears, she was a charming actress. As I said, he loved her, and she didn’t care for him a whit. This he came to know soon after they were married. So, Arianne, to understand the rest, let me ask you a question. Did you love your husband?”

Arianne knew lying would be of no use. “I did not.”

“And did he know it?”

“Yes.”

“And was he miserable?”

“No.”

“So let’s reason it out. Davon Carver was miserable when he came to court last year. What does that tell you about him?”

“He loved her. But how could he? He knew by then what she was!”

“Tsk, tsk, dear. Why is not the issue! That you should even ask such a thing shows me your heart has never been touched. Listen. This same miserable man who had every right and every reason to divorce his wife instead chooses to fake his death and forsake his title, his lands, and the prosperous estate he’d resurrected from nothing. He left it all to her, mind you, to work as a common clerk in a rat infested warehouse. So, dearest Arianne, I believe that leaves us with two choices as to the nature of Mr. David Harper’s character, neither of which is a shameful coward. He is either…”

“A madman.”

“Or…”

“The most generous man in the world.”

“Exactly,” the Queen replied. “Though at the moment I think it might be a little of both. A bad marriage can do wretched things to a mind.”

Silence fell between them as the Queen returned to her window. Arianne abandoned the now cold tea for good. It made no sense. How could he love a woman who had spitefully used him to rescue her from her indiscretions? He’d won her honor back for her, legitimized it by marrying her, gifted her a life of prosperity—his hard fought prosperity—and then disappeared so she could enjoy it. Unfathomable. Absolutely ridiculous. He had to be out of his wits.

“So what are you going to do?” Arianne asked while wondering the same thing for herself. “If someone else recognizes him, it could turn ill for you and the widow Carver.” Whom Arianne was now disposed to hate.

“Perhaps. The truth is I have plans for him. He has already been of much more use to the Kingdom as a clerk than he ever was as a Lord with all his in absentia voting. I doubt he stepped foot in the parliament house once. Ironically, he’s spent more time at court in the last few weeks than he did his entire life before. As for his identity, widow Carver is really the only one I worry about, though I’d wager she is so happy to be rid of him that she wouldn’t say a word even if she did suspect he were still alive.”

“I hope to never see her,” Arianne stated firmly.

Filippa laughed. “And what about him? Do you think you can abide his presence?”

“Honestly, I don’t know what to think. The whole business is so singular! It will take time for me to sort it out.” Whatever her own feelings, it was clear that the Queen of Bellshire had no objections at all with Lord Carver’s actions and even admired them.

Filippa nodded in a motherly, understanding fashion at Arianne’s perplexity and sat next to her on the couch, patting her hand.

“Well, sort them out you must. I hope you don’t take offense at what I ask of you. I need Lord Carver—well, the clerk David Harper—to go to your estate in Hightower and have a look at your husband’s ledgers. The late Lord Hightower was one of the principals behind this little Aid Society we’ve all so generously contributed to for the last few years, and I would like to settle my mind about your husband’s involvement. I’ll need you to be there to handle your steward and clerk—perhaps send them away for a holiday.”

Arianne was a little surprised, but the more she thought about it, the more the Queen’s inquiry made sense. “Why Lord…why Mr. Harper?” It would be hard to address him properly now.

Filippa smiled. “I need him gone before his soon to be engaged wife comes to court next week, and as an underclerk and someone not well known, his absence from Bellshire won’t attract too much undue attention.”

“As you wish. When should I leave?”

They both stood, their meeting coming to a close. “In a couple of days. I’ll send Mr. Harper to your door a few days after that when Widow Carver is set to arrive. And please remember the discretion you swore to.”

Arianne curtsied. “I will.”

“I’ll see you at the ball tonight, Arianne. Good day.”

Arianne left, mind spinning. While she didn’t feel justified in judging Lord Carver, she resolved it would be best to simply avoid him as much as possible to spare them both the awkwardness that would result if they were to meet more than absolutely necessary.

Chapter 13

There were two positions to which commoners might be chosen and earn the title of Lord. Lord Ember, guardian and caretaker of the Eternal Flame, was one. Lord High Sheriff was the other. The Eternal Flame itself chose Lord Ember, so there were never disputes when a commoner was elevated, but selecting a Lord High Sheriff, nominated by the monarch and ratified by the House of Lords, often turned into a political struggle. The House of Lords generally looked down on elevating commoners to anything, and the Lord High Sheriff held enough power and prestige that many of the nobility coveted the assignment.

When Queen Filippa had nominated Oliver Campbell, an experienced sheriff of Bellshire, she had expected the usual rounds of debates, threats, counter nominations, and excessive blather that could turn a simple task into a nightmare that stretched out for weeks. Fortunately, Oliver’s golden reputation from two decades-worth of peaceful Bellshire streets, in addition to the marks of the Flame upon his palms, rendered opposition to his appointment nearly impossible. The House of Lords had ratified Oliver Campbell in what Queen Filippa reckoned was record time.

The Lord High Sheriff was an imposing man with a silvery, curling mustache and iron gray hair. He wore his black and gold uniform with dignity and pride, though a tailor had adjusted the size of his pants and coat several times; he had no occasion to personally chase down criminals through the streets of Bellshire, and the plentiful larder of a Lord was simply too hard to resist. Rich food excepted, Oliver Campbell was a man of strict control and strict schedule. He had performed admirably in the four years since his appointment, and Filippa appreciated that this one decision of hers went uncriticized by the cantankerous House of Lords.

They walked together out of the palace toward the offices of the anatomist where they would inspect the bodies of the failed assassins. The weather was just as pleasant as the day before, and Filippa squinted in to the sunshine as light flooded around her, eyes tired from a night spent thinking rather than sleeping.

Not one person had been killed in the Harrickshire attack. Each would-be assassin shot only once, and all but one had missed. The third had only managed to graze a serving man. While the nobles were quick to thank the Flame for their good fortune, Queen Filippa harbored gnawing doubts.

“Were you able to make anything of their personal effects, Oliver?” she asked.

He twisted one tendril of his mustache between two fingers. “They were nondescript to a fault, Your Grace. The horses were of common stock

, and their clothes and personal effects were of country make that would be found on either Creetisian or Bittermarchian commoners. There were no journals, books, or letters of any kind on their persons that would provide any clues as to their origins or motivations. Our best guess is that the rifles were of Bittermarchian make, but I could not prove it. I wish the Earl had not been quite so good of a shot. We could have used one of them alive. Damn fine shooting, though.”

The Queen nodded. Ambassador Horace Clout was a player of political games, and Filippa was beginning to realize that the fiery, annoying Creetisian representative might have actually started something serious this time. Her discernment, a gift from the Flame that the sheriff shared, told her plainly that the Ambassador’s accusations of slaughter were a fabrication, but too often people acted like sheep, willing to obey any shepherd with a title and a loud mouth. In this case, Filippa needed absolute proof of Horace Clout’s duplicity. His speech with the House of Lords fell on more sympathetic ears than she had hoped, especially when he had tried to paint her as a raving, religious lunatic out of control.

Due to the unsavory nature of what an anatomist must do, the anatomist’s building was separated from the Lord High Sheriff’s offices in the Royal Park and was almost universally avoided. Despite diligent care by the anatomist’s assistants, a peculiar odor always emanated from the edifice and leaked into the street. Oliver’s long association with such smells and sights had rendered him oblivious to the discomfort they caused everyone else. Filippa wasn’t so accustomed to the reek, and her stomach soured as Oliver opened the door for her.

The bottom floor was a functional, though finely appointed, office. A set of stairs led up to the anatomist’s laboratory. He had refused to work in the basement. He wanted windows and light, though cutting up human corpses simply couldn’t be done on the ground floor where passers-by might a view a vomit-inducing eyeful through a window. This arrangement forced the anatomist’s assistants to haul the corpses upstairs for examination and then back down to the basement for incineration.

An assistant guided them up the stairs, and as they ascended, they could hear singing; Anatomist Norris Breakman wasn’t, in the Queen’s estimation, altogether in his right mind. She wondered how anyone who spent their life hacking up dead bodies for clues could be in their right mind. The smell and the singing got stronger as they approached a single, uncomfortably stained door.

Twenty-three corpses under the tree.

Drag one off and bring it to me.

Cut it open so I can see

What’s in the corpse that was under the tree.

Twenty-two corpses under the tree.

Drag one off and bring it to me.

Cut it open so I can see

What’s in the corpse that was under the tree.

Twenty-one…

The assistant opened the door and the anatomist cut off his macabre melody in mid-stream. Norris Breakman, while nearly as old as the High Sheriff, had the enviable gift of seeming much younger than his age. His messy black hair had yet to show a streak of gray, and large blue eyes remained untouched by dark circles or crow’s feet. The Queen saw him little, but he always seemed happy and well rested, his good mood as implacable as his good health. The three assassins lay on tables before him.

“Your Grace,” he said excitedly. He stuffed a wad of intestines back into a body on the table and wiped his hands on a thoroughly befouled leather apron. “Top of the morning to you! And Lord High Sheriff! Welcome, welcome. Can I get you something to drink?”

How could anyone eat or drink anything in this place? the Queen wondered. “No, Mr. Breakman. What can you tell me about these three men?”

“Well! I’ve worked through the night examining these fellows. Skinny little chaps they are. Ugly, too. Unshaved. Not very well endowed, if you take my meaning. Quite plain and unremarkable. But you know, it took me a solid hour just to get past their wounds! One shot each to the right side of the head, all of them within four inches of the ear! Four inches! Most of us would be lucky to do that to a sleeping cow from ten feet. But three times from 100 yards to men at a full gallop! Remind me not to step on the Earl’s toes!”

The High Sheriff was growing impatient. “We’re well aware of the extraordinary circumstances of their demise. We are interested in their origins, if you could get to the point.”

Mr. Breakman laughed, apropos of nothing. “Well, some interesting things, of course, came up in my examination.” He lifted up the hand of the corpse in front of him. “Note, if you will, the fingernails. Ridged, coarse, brittle. Poor nutrition indicative of a poor diet, more common in outlying areas where there isn’t a good variety in the fare. Definitely indigent, simply deduced by the unfortunate state of their hygiene.” He pried open one of the mouths. “Yellowing, crooked teeth, little decay. Not a lot of sweets in the diet. Hair roughly cut, probably by a sharp knife. But most interesting for your purposes was what I found in the digestive tract!”

He reached a hand into one of the man’s guts, but the High Sheriff brought him up short. “Just tell us, Mr. Breakman. We’ll take your word for it.”

“Ah! Sorry! My enthusiasm gets the better of me. Due to our agricultural preferences here in Bittermarch, and due to the longer growing season, our wheat is more refined. Creetisian wheat is heartier, coarser, and has more hulls. These men ate bread of the Creetisian variety, I am sure of it. And their general undernourished state seems to correspond with what we know about the agricultural difficulties in Creetis.”

“Very interesting, Mr. Breakman, thank you,” the Queen said, ready to be gone.

“It’s my pleasure! I’ll inform you of any further developments.”

They left quickly, Mr. Breakman resuming his song where he left off.

“So what do you make of Mr. Breakman’s information?” the Queen asked the sheriff.

“Almost certainly Creetisian, perhaps trying to masquerade as Bittermarchians. We still have more questions than answers. Perhaps they were from Creetis seeking revenge for the alleged massacre. Certainly not professionals or even competent. Without more information, it will be hard to connect them to a larger plot, if there is one.”

The Queen was grateful for the fresh air as they emerged from the building. She wanted rest. She had hoped the last years of her rule would be as untroubled and peaceful as her previous twelve years of service, but it was not to be. So many troubles and so much strife. At least she had the drama of Baron Carver to offer some amusement.

Chapter 14

The sun had set on Mr. Lambert’s office in the palace, the warm evening light fading and candles ignited to life by the clerks finishing their last tasks of the day. Davon sat among them, finishing an audit of a three year old ledger of the palace’s laundry expenses. Not exactly the kind of job that got the blood pumping. While the Boot and Wheel Caravan Company was a depressing place, its irascible employees and nefarious deeds had kept it interesting.

Music from the evening ball filled the palace, barely discernible from where he and the clerks and underclerks busily scribbled their sums and filed their papers. While the Queen’s general clerkship was, to a man, an affable lot, Davon struggled to find common ground with his office mates. They had their clerking stories and tales about family and friends; Davon had one clerking story, a handful of lies, and very little else he could divulge without risking discovery of his identity.

Working ten to twelve hour days six days a week left little time for excursions to his beloved outdoors, and while the schedule and the office could hardly be called grueling or unpleasant, he often found his concentration floating out the window. The sunshine, mountain valleys, and unexplored canyons constantly tried to seduce him away from his desk, and if he couldn’t be of any real use to the Queen, he thought seriously of asking for a transfer.

Despite his mounting dissatisfaction, Davon did his work the best he could, and as the low man in the office hierarchy, he endured plenty of scrutiny until Mr. Lambert dee

med the newest underclerk competent enough to do “the basic but utterly necessary duties.” These included audits of minor palace departments and running up and down the palace collecting purchase receipts from every office and officer that had claims upon the Queen’s treasury. The constant errands, while hardly stimulating, at least provided some excuse to uncramp his long legs.

“I say, Mr. Harper?”

Davon glanced up from his ledger and food purchase receipts, finding Mr. Lambert with an excited expression on his face.

“Yes, Mr. Lambert?”

“It is rather astonishing,” he said, fumbling with a note in his hand, “but you’ve been summoned to the Flame Cathedral by Lord Ember himself. This instant! You realize what this means, don’t you?”

Davon had an idea, but wondered what Mr. Lambert was thinking. “That Lord Ember wishes to know—”

“That you are to undergo the test!” Mr. Lambert butted in. “That’s the only explanation. Think of it! You might rise from a clerk at some disreputable establishment to a member of the House of Light!”

The Test. The opportunity to approach the Eternal Flame to see if it would choose you to be Flametouched, marked on the palms and endowed with a gift. The though thrilled him. Few had the privilege of approaching the Flame so intimately, and even if it did not select him, the opportunity would be an honor he would remember forever.

There was only one downside in his mind. Those chosen by the Eternal Flame automatically garnered a seat in the House of Light, which the Queen had, during her reign, elevated above the House of Lords in matters of voting. Davon had no desire to enter politics again, if it could be claimed he had entered it at all.

As a Baron, he had attended the House of Lords but once and tired quickly of the posturing and small-minded infighting. The most innocuous of cases caused lengthy debates about minute particulars, and it drove Davon mad. He had commented to Emile that the real reason nobles had cooks was not because they could not do the work, but that if left to themselves they would starve to death arguing over what to prepare.

Flametouched

Flametouched